*Not really

As I age, I tend to get lazier as a guitar player. I like to rely on patterns. A lot. This laziness isn’t completely unwarranted. I mean I do love everything about guitars. Playing them. Hearing them. Looking at them – guitarcenter.com is like a girlie mag for my old age. However, I realized long ago that I would never be a hotshot guitar player no matter how much all the guitar mags want me to think I can be. And as I got older, I realized that putting a great deal of effort into memorizing tons of different shapes no longer holds appeal for me. Then one day, while procrastinating working, I was reading a guitar thread where a user briefly mentioned how major keys can be made up of other scales found within that particular set of notes.

Intrigued, I started thinking about it.

I thought about it a lot. Heck, I even made an excel spreadsheet as a visual aid.

Excel spreadsheet, you say. Wow it must be serious. Show me a PowerPoint presentation.

Hey let’s not get carried away for gosh sakes, it’s only guitar stuff.

What if I told you I discovered the Ark, the Fountain of Youth, and the Holy Grail of guitar playing? And, unbelievably, it was based on the one scale pattern most guitar players probably already know? At first I seriously doubted my hypothesis, because I really thought this concept was much too easy an explanation to actually be worth anything musically. Like it was such an obvious answer to navigating the fretboard that there was no possible way it would actually work. I don’t recall ever reading about this idea in the guitar magazines or music theory books I have read. It was like Cold Fusion and just didn’t seem like it should be workable. But the idea was intriguing and kept pulling me back. Like the movie Inception but with strings and tuners. I had to investigate to see if I was onto something or if this was just some tinfoil-hatted theory. So I started doing the (sigh) work and made the aforementioned chart found below.

Let’s get to it.

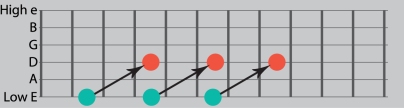

This idea hinges on the fact that you already know the difference between major and minor pentatonic scales and how both can be played using the same pattern, but starting on different frets. In this situation, the same pentatonic shape can work as both major and minor depending on which note is considered the root. Root on the index finger – the scale is minor. Root on the pinky – the scale is major. For example A-Minor pentatonic starts on the 5th fret of the low E string. If you take this pattern and move it three frets toward the headstock you are in A-Major. How’s that for versatility? I like to use a couple different pentatonic patterns, but that’s the nice thing about guitars. Scale shapes like this are easily movable and adaptable based on your level of fretboard knowledge. For our purposes remember, minor scales are considered the same as their relative major scales.

Now for the chart. Listen carefully.

The top row lists the all of the triads that make up the harmonized C-Major scale (I, ii, iii, IV, V, vi, vii°), but you can move this to any major scale. In the columns below the triad names, I have listed the corresponding major/minor pentatonic scale that will work over that chord when played within the context of a chord progression. Then, depending on whether the chord is major or minor, you can use those scales that correspond with the root of the chord. If the chord is major, use the major pentatonic. If it is minor, use the minor pentatonic. Say you are in the key of C-Major. If the chord sequence is using a ii (D min) chord, you can use the D-minor pentatonic scale over that chord. The corresponding scales are comprised of notes found in the major scale used in the main composition. I have color-coded the columns so you can see that none of the notes in the various pentatonic scales are outside of the notes within the “parent” scale of C-major. Interestingly, this approach is almost like being able to understand the modes, (you know – Oneian, Twoian, Threegian, Fourdian, Fivolydian, Sixolian, Loyoucrazian), without actually having to understand the modes.

Now, understandably, this may be a little simplistic for an advanced player. However, for a beginner, or for a non-hotshot guitarist like myself, it is a pretty easy way to grasp the concept of playing to the chord changes rather than staying in the same position throughout an entire progression. Additionally it will help with fretboard fluidity and fluency. The nice thing about this approach for the learning guitarist is that it doesn’t require memorizing a ton of different shapes. Knowing one or two pentatonic shapes and how they can be moved from major to minor is all it requires and should give you a pretty good start to moving around the neck while learning to stay in key over the changes. Give it a try.

Professor P.

-World’s okayest, self-taughtiest, basement-leveliest guitar player.